TruQuick™ HBsAg/HCV/HIV/Syp

TruQuick HBsAg Component is a rapid test to qualitatively detect the presence of HBsAg in serum or plasma specimen. The test utilizes a combination of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to selectively detect elevated levels of HBsAg in serum or plasma. Viral hepatitis is a systemic disease primarily involving the liver. Most cases of acute viral hepatitis are caused by Hepatitis A virus, Hepatitis B virus (HBV) or Hepatitis C virus. The complex antigen found on the surface of HBV is called HBsAg. Previous designations included the Australia or Au antigen.1 The presence of HBsAg in serum or plasma is an indication of an active Hepatitis B infection, either acute or chronic. In a typical Hepatitis B infection, HBsAg will be detected two to four weeks before the ALT level becomes abnormal and three to five weeks before symptoms or jaundice develop. HBsAg has four principal subtypes: adw, ayw, adr and ayr. Because of antigenic heterogeneity of the determinant, there are 10 major serotypes of Hepatitis B virus. TruQuick HCV Component is a rapid test to qualitatively detect the presence of antibody to HCV in a serum or plasma specimen. The test utilizes colloid gold conjugate and recombinant HCV proteins to selectively detect antibody to HCV in serum or plasma. The recombinant HCV proteins used in the test kit are encoded by the genes for both structural (nucleocapsid) and non-structural proteins. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) is a small, enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA Virus. HCV is now known to be the major cause of parenterally transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis. Antibody to HCV is found in over 80% of patients with well-documented non-A, non-B hepatitis. Conventional methods fail to isolate the virus in cell culture or visualize it by electron microscope. Cloning the viral genome has made it possible to develop serologic assays that use recombinant antigens.2, 3 Compared to the first generation HCV EIAs using single recombinant antigen, multiple antigens using recombinant protein and/or synthetic peptides have been added in new serologic tests to avoid nonspecific cross-reactivity and to increase the sensitivity of the HCV antibody tests.4

- Bring the pouch to room temperature before opening it. Remove the Test Cassette from the sealed pouch and use it as soon as possible. Best results will be obtained if the assay is performed within one hour.

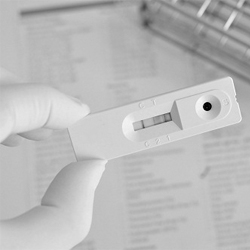

- Place the Test Cassette on a clean and level surface. Hold the dropper vertically and transfer 2 drops of serum or plasma (approximately 50 μL) to the specimen area, then add 1drop of Buffer (approximately 40 μL), respectively. Start the timer. See the illustration below.

- Wait for the colored line(s) to appear. The test result should be read at 10 minutes. Do not interpret the result after 20 minutes.

- Blumberg BS. The discovery of Australian antigen and its relation to viral hepatitis. Vitro. 1971;7:223.

- Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science.1989;244:359.

- Kuo G, Choo QL, Alter HJ, Houghton M. An assay for circulating antibodies to a major etiologic virus of human non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science. 1989;244:362.

- van der Poel C L, Cuypers HTM, Reesink HW, and Lelie PN. Confirmation of hepatitis C virus infection by new four-antigen recombinant immunoblot assay. Lancet. 1991;337:317.

- Wilber JC. Development and use of laboratory tests for hepatitis C infection: a review. J Clin. Immunoassay. 1993;16:204.

- Chang SY, Bowman BH, Weiss JB, Garcia RE, White TJ. The origin of HIV-1 isolate HTLVIIIB. Nature. 1993;363:466-9.

- Arya SK, Beaver B, Jagodzinski L, Ensoli B, Kanki Albert, Fenyo J, et al. New human and simian HIV-related retroviruses possess functional transactivator (tat) gene. Nature. 1987;328:548-550.

- Caetano JA. Immunologic aspects of HIV infection. Acta Med Port. 1991;4 Suppl 1:52S-58S

- Janssen RS, Satten GA, Stramer SL, Rawal BD, O’Brien TR, Weiblen BJ, et al. New testing strategy to detect early HIV-1 infection for use in incidence estimates and for clinical and prevention purposes. JAMA. 1998;280(1):42-48.

- Travers K, Mboup S, Marlink R, Gueye-Nidaye A, Siby T, Thior I, et al. Natural protection against HIV-1 infection provided by HIV-2. Science. 1995;268:1612-1615.

- Greenberg AE, Wiktor SZ, DeCock KM, Smith P, Jaffe HW, Dondero TJ, Jr. HIV-2 and natural protection against HIV-1 infection. Science. 1996;272:1959-1960.

- Fraser CM. Complete genome sequence of treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science. 1998;281 July:375-381.

- Center for Disease Control. Recommendations for diagnosing and treating syphilis in HIVinfected patients. MMWRMorb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 1988;37:601.

- Johnson PC. Testing for syphilis. Dermatologic Clinic. 1994;12 Jan:9-17.